RUSSELL JAMES

REDWOOD

HARRIS

Russell James Redwood Harris (b. 1983, Romney Marsh, Kent, England) is a Berlin-based, self-taught multidisciplinary artist working with textiles, leather, sculptural objects, and installation. Born on Romney Marsh—an area known for its sparsely populated wetlands, woodlands, and coastal marshes—his early environment, coupled with a family culture of making and mending, left a lasting impression on his relationship to materials, process, and care. Harris’s practice explores themes of transformation, ritual, and myth, often integrating sensory elements to evoke personal, visceral, and universal narratives. Since 2015, he has worked as a production assistant to Mark Krayenhoff van de Leur and his husband, the artist A.A. Bronson—a long-standing collaboration that continues to shape his approach to craft, collaboration, and queer lineage.

Artist

RUSSELL JAMES

REDWOOD

HARRIS

FEATHERS

Harris’s hand-cut leather feathers are an ongoing and evolving body of work that began in 2015. Over the ensuing years, their production has become a regular practice—and as with many committed endeavours—has become a container for noticing change. For Harris, this change is manifest in both the shape and refinement of the feathers and the qualities of his thought processes.

Collectively, they make something of an odometer for psychic and spiritual evolution, their forms showing a subtle, slow, and ongoing transformation. The feathers also hold deeply personal significance, rooted in loss and endurance. Harris’s mother, Glynis, began collecting white feathers after the passing of her own mother, seeing them as signs of angelic presence. Harris recalls finding these feathers tucked into picture frames or perched on window sills—quiet tokens of her belief in unseen connections. After Glynis’s death in 2015, Harris began crafting his own feathers as a way to honour her memory and reflect on the enduring bond they shared.

In 2017, Michael Howells, a respected production designer and mentor figure, commissioned 200 feathers for Karl Lagerfeld’s Christmas installation at Claridge’s Hotel in London. This marked a turning point in the visibility of Harris’s work and remains a meaningful endorsement of his practice.

NESTS

Harris’s nest installations were developed following a 2022 trip to Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park, where he encountered intricately constructed, multi-storey nests made by weaverbirds. These sociable birds build sprawling, multi-compartment suspended structures, each with flask-shaped chambers that house up to 100 breeding pairs across generations. Harris was drawn to the relationship between the large-scale organic forms these nests become, the refined and detailed actions that build them, and the social systems their emergent designs reflect.

In response, he began crafting his own nest works using raffia straw, through a process of sorting, knotting, winding, crocheting, and latch-hooking. These repetitive gestures—both intuitive and skilled—echo traditional textile practices while evoking the instinctive labour of communal construction. The resulting forms feel at once ancestral and adaptive, pointing toward alternative architectures, kinship models, and shared ways of living.

For all photos

Nest installation view from those are the skeletons

that spoke to me - solo exhibition, Kulturraum,

Berlin

2023

Raffia, wood and steel.

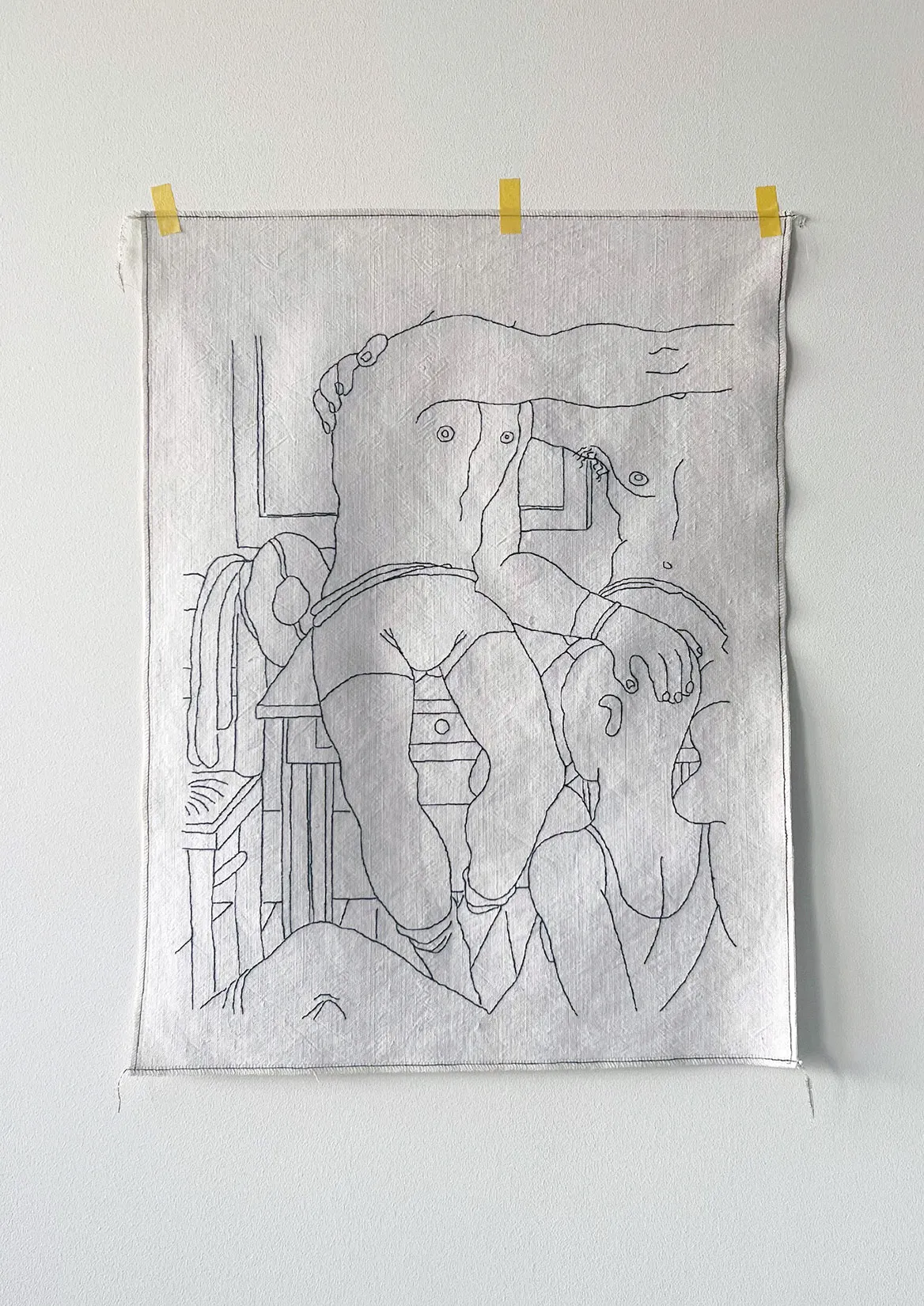

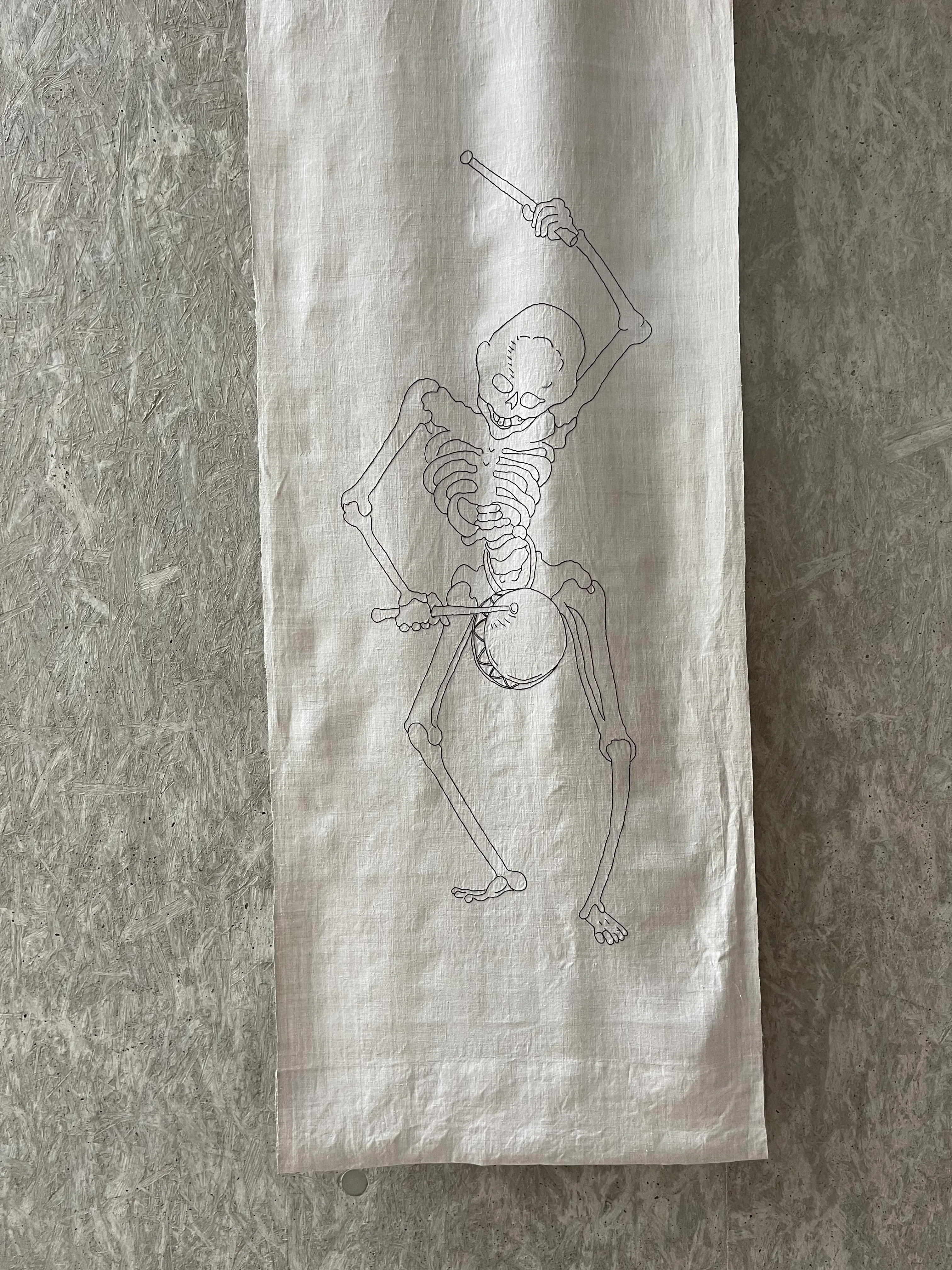

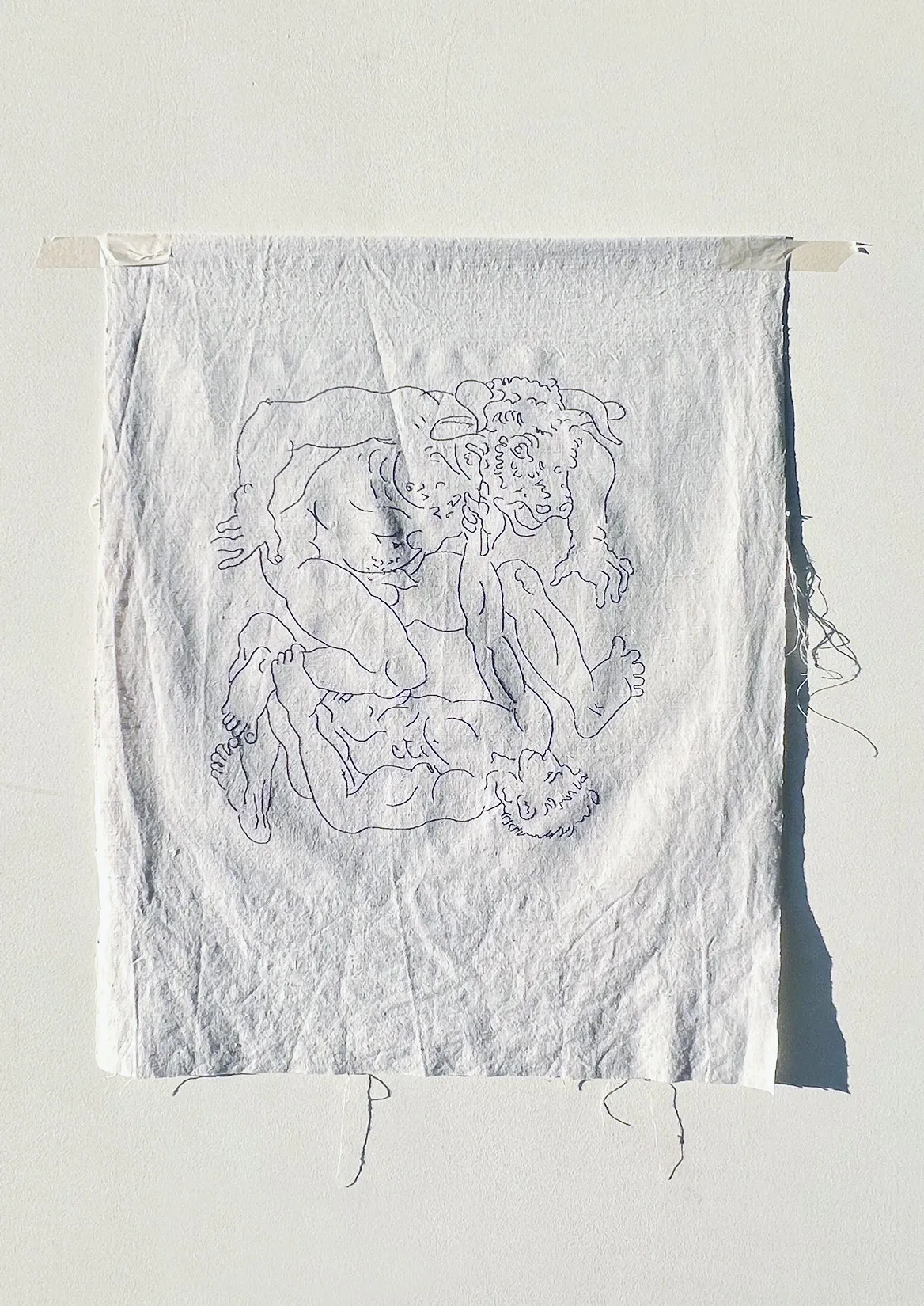

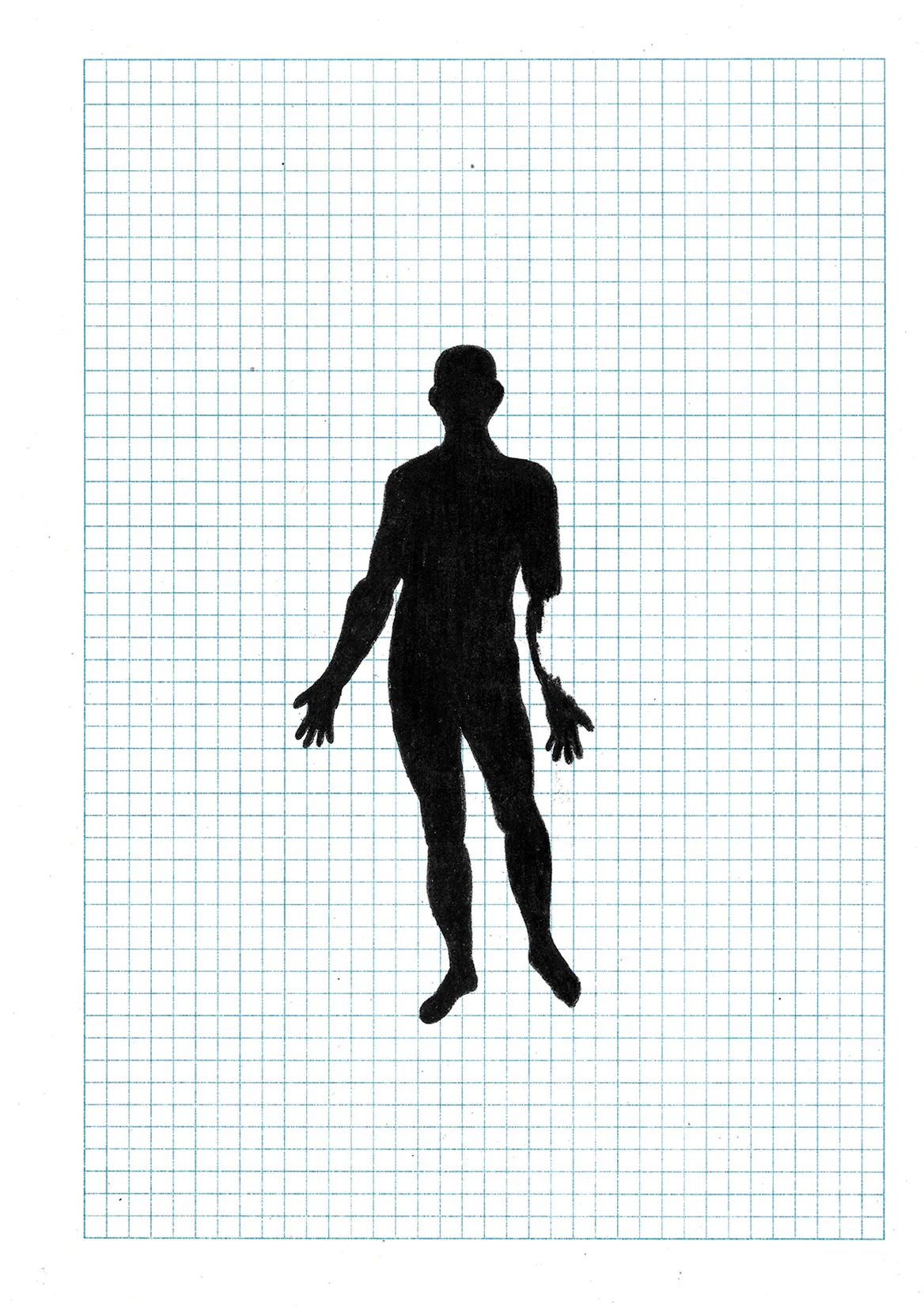

Dance of Death (Holbein Embroidery)

This embroidered textile is based on The Dance of Death, a 16th-century series of woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Younger, where death is rendered not as solemn, but lively, disruptive, and always near. Harris reworks Holbein’s linework into embroidery on linen, translating the figure in thread as an act of study.

Skeletons recur throughout Harris’s practice—as emblems of shared anatomy and impermanence, stripped of power, status, or surface. Today, they feel harder to look at—echoes of ongoing loss and grief, unfolding far beyond the work.

For Harris, embroidery is a way of learning through the hand–eye connection: the work is a study, shaped by observation, repetition, and engagement with the multiple lines that run through our visual and symbolic pasts. This work sits within a wider effort to stay in relation to past images — not to preserve what’s already known, but to engage, respond, and re-see.

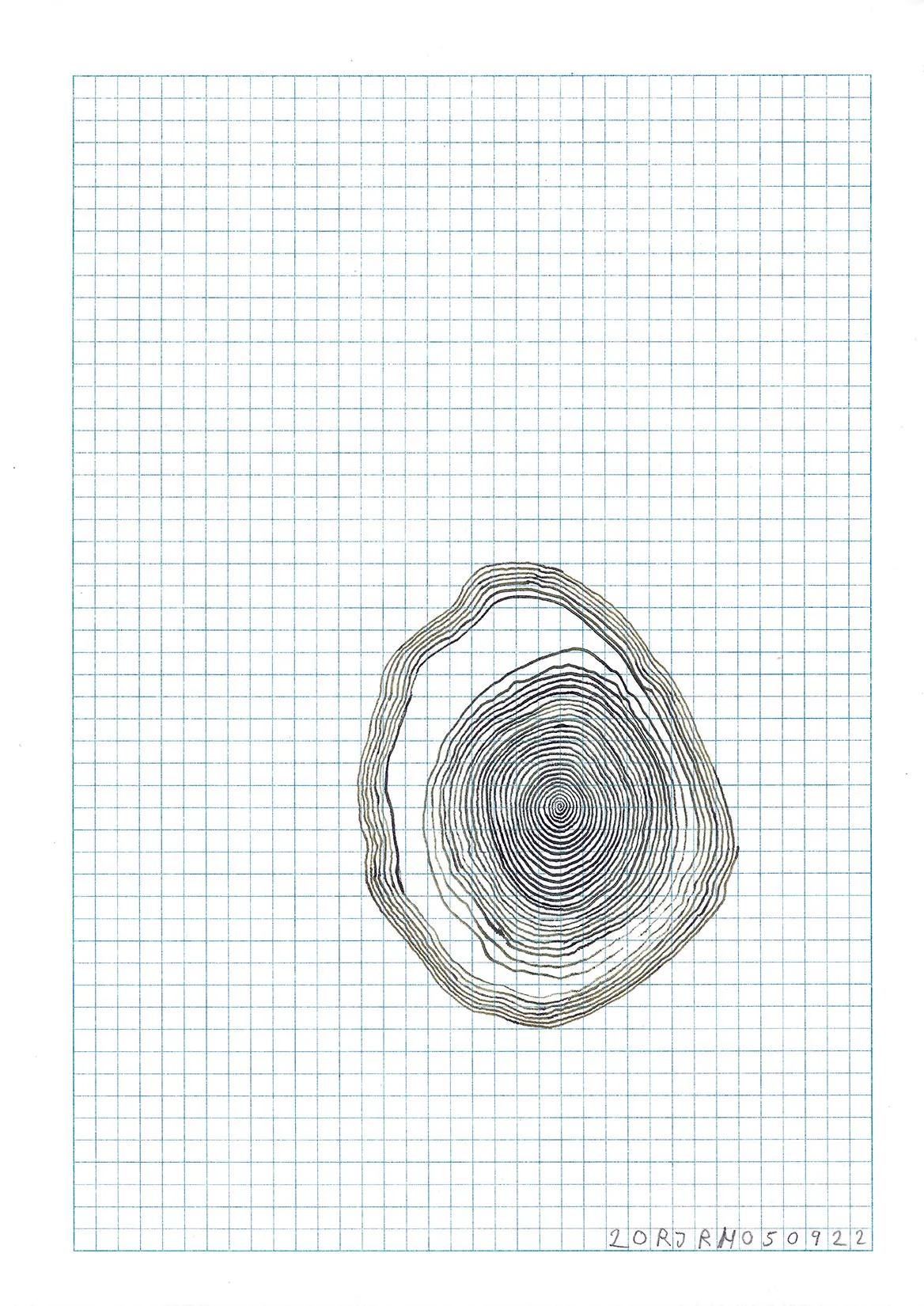

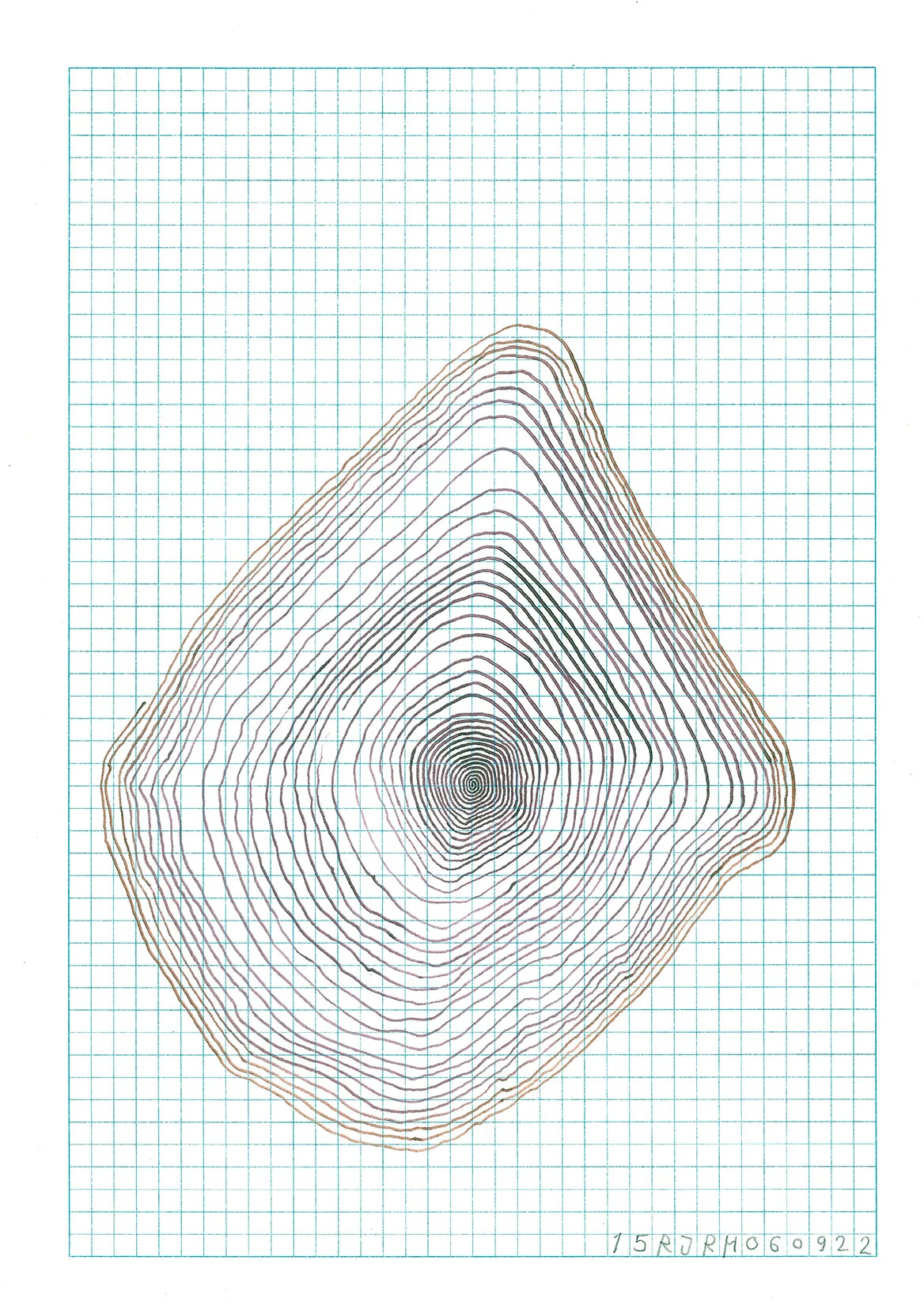

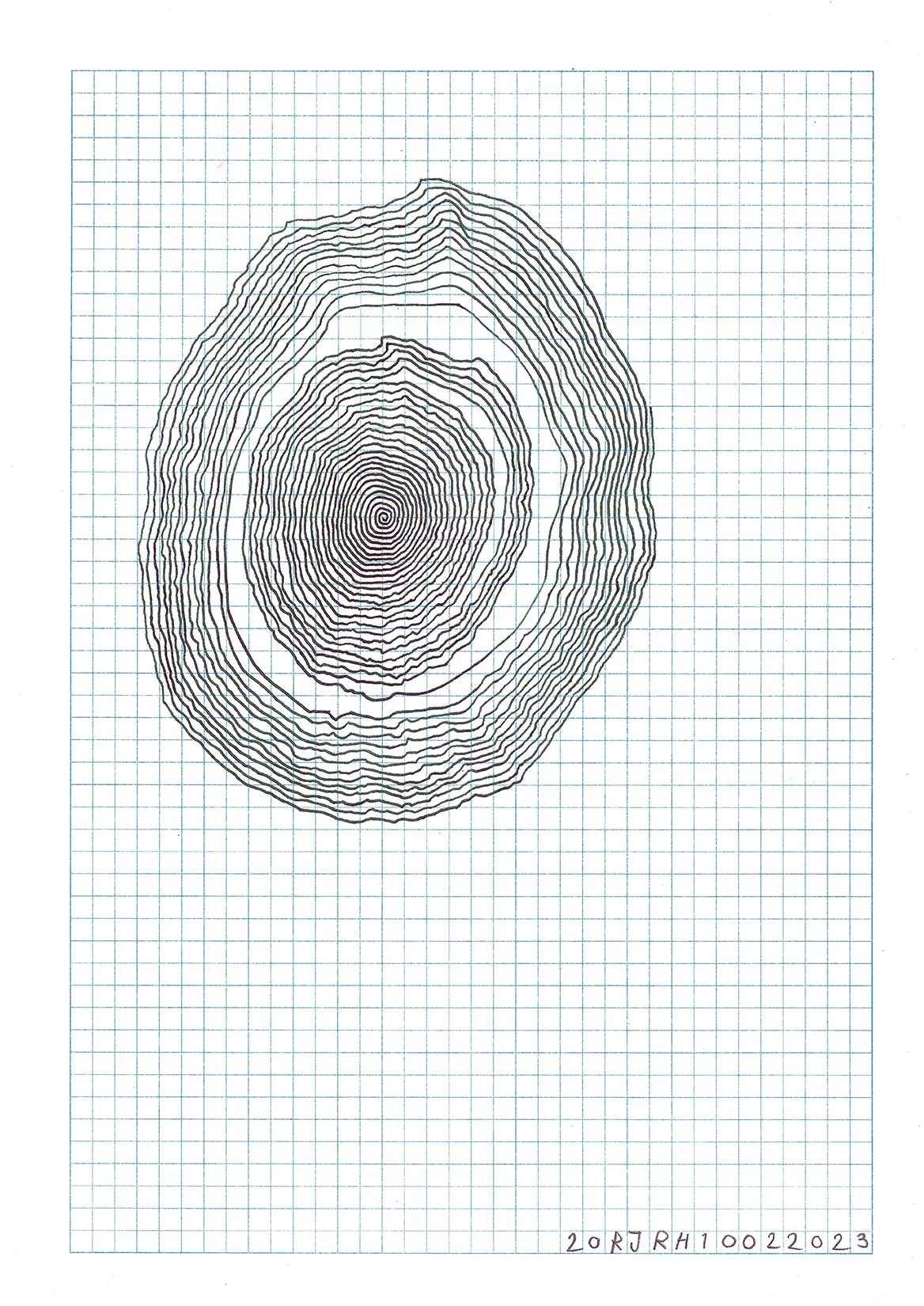

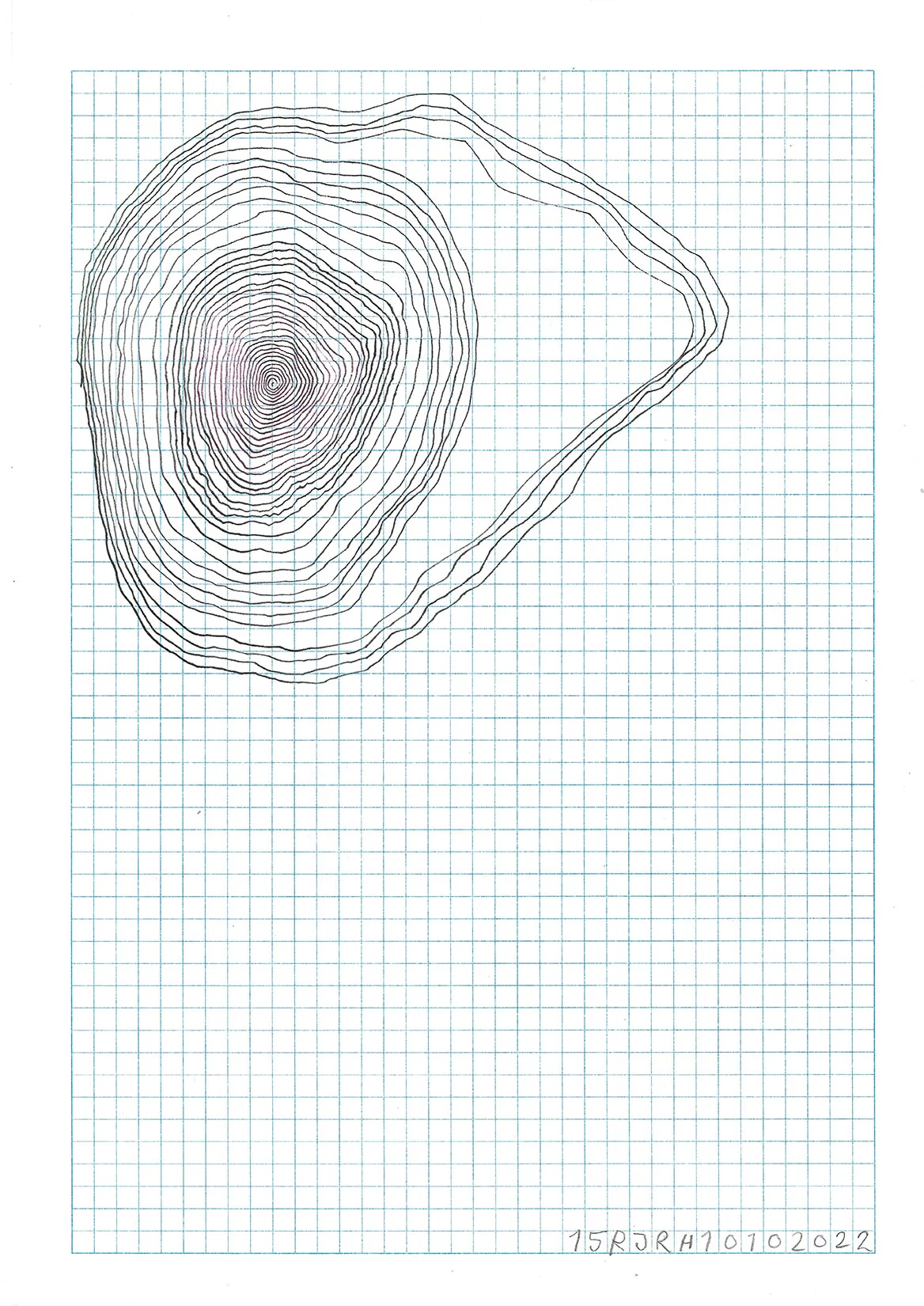

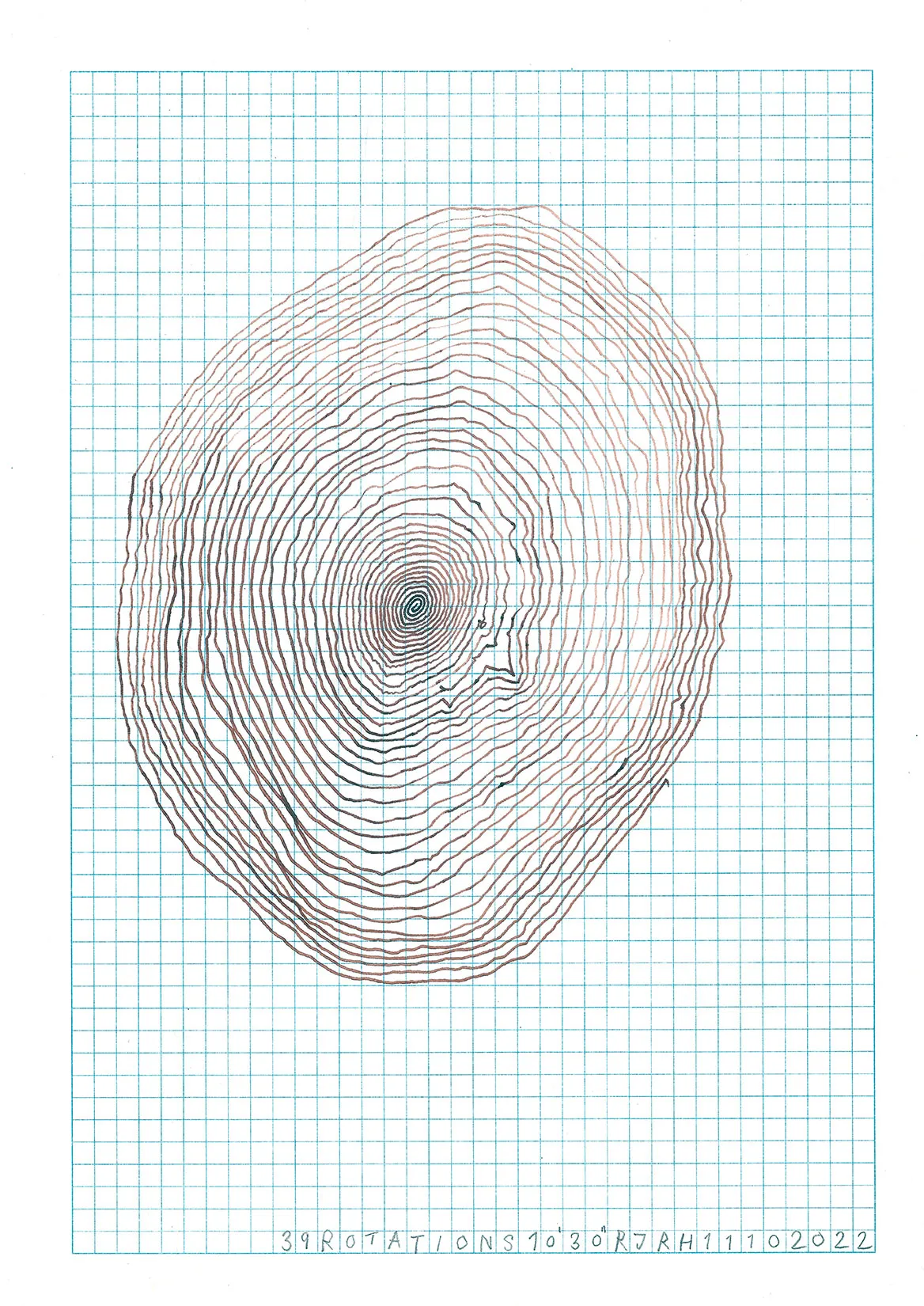

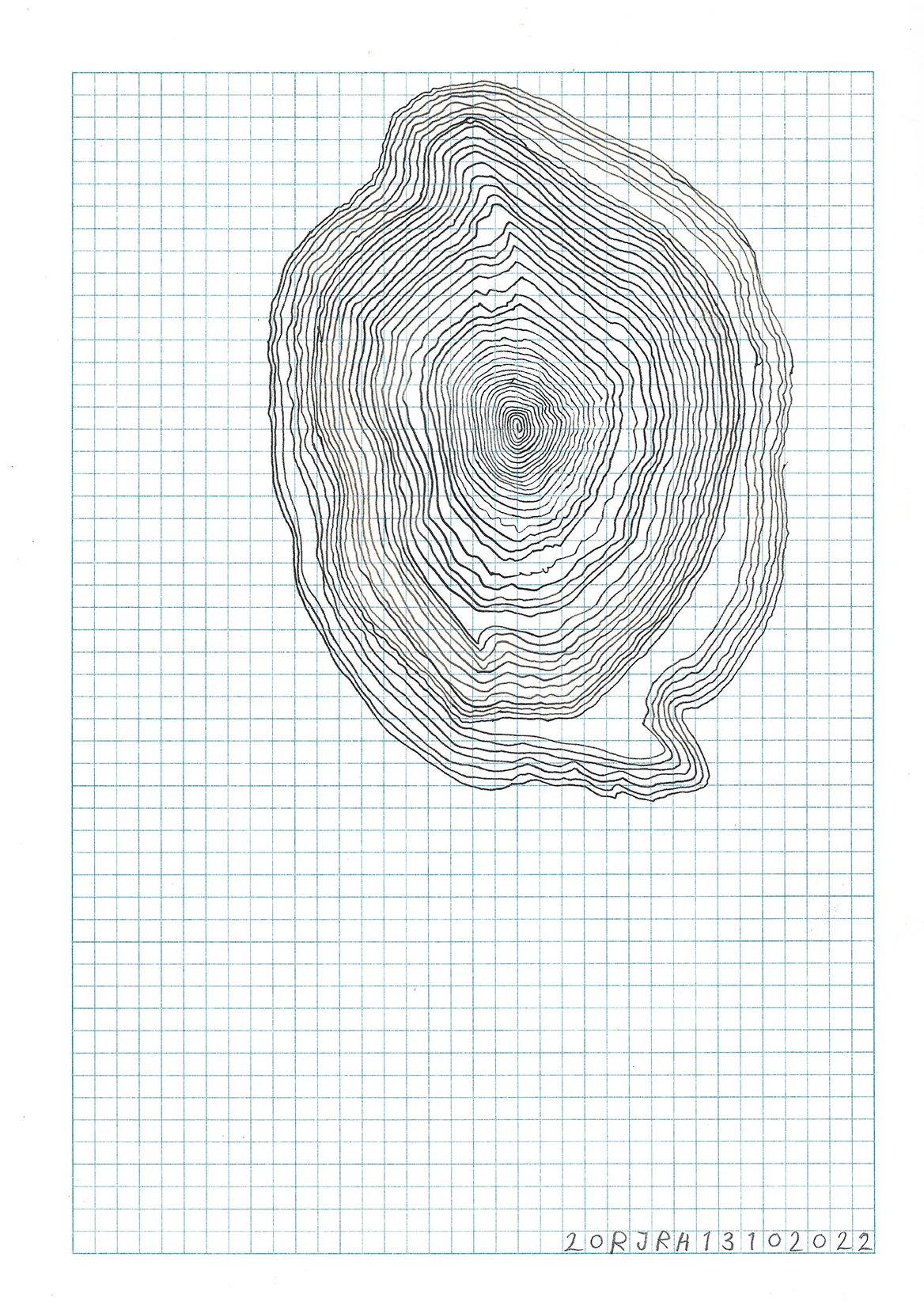

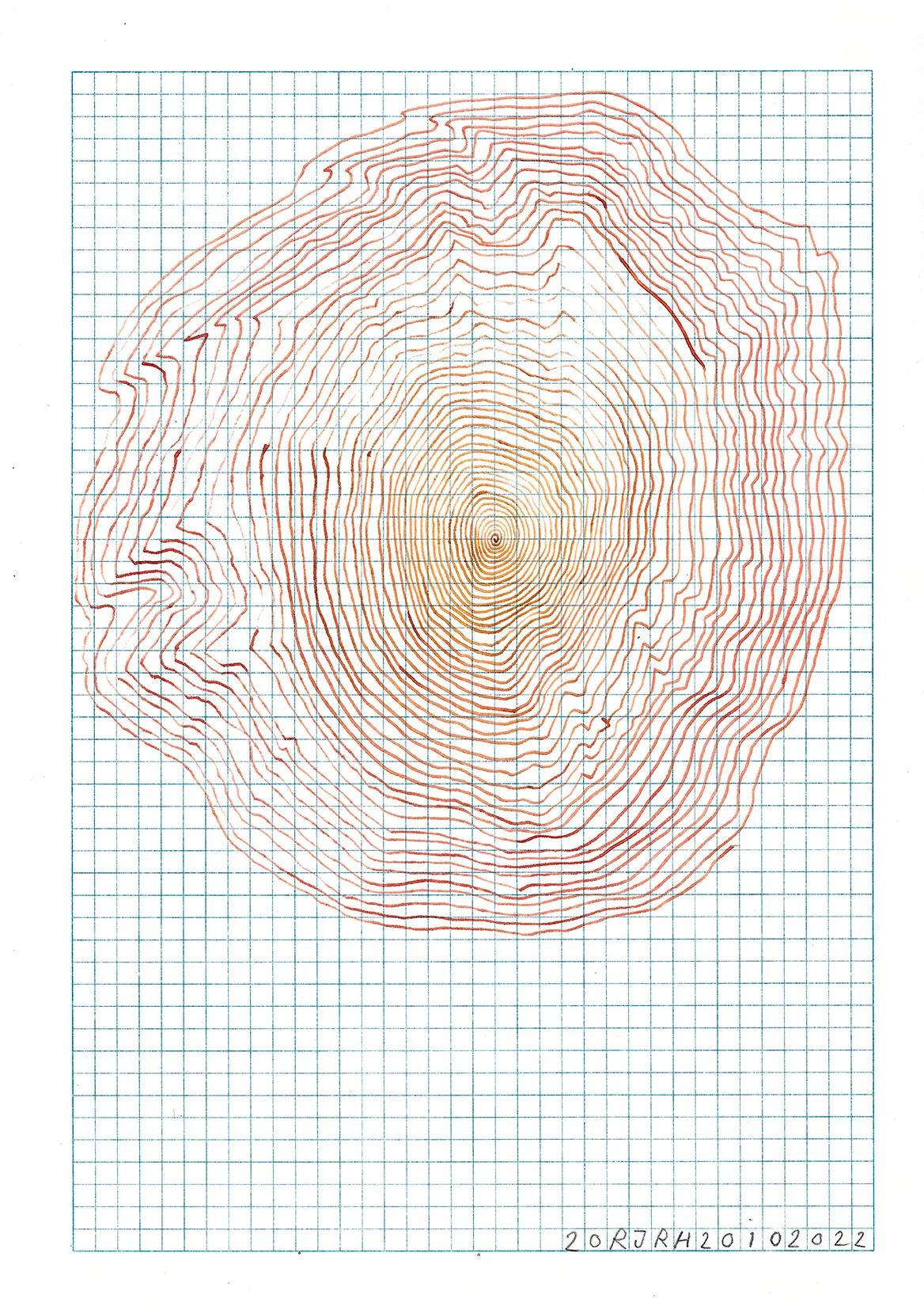

DRAWINGS

The Spiral Drawings are made with archival ink on vintage graph paper sourced from Berlin’s flea markets. Harris undertakes these drawings as a regular 10, 20 or 30 minute meditative practice, where each image emerges differently and organically with time, tension, attention, and breath.

Rather than artistry or design, he is interested in how these labours—their specific conditions and states of mind—leave behind a trace: like a watermark, a topographical map, or the rings of a tree trunk. These drawings are not illustrations but residues of presence, and potential aids to contemplation.

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

INK ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

2022

CARAN D’ACHE LUMINANCE 6901COLOURED

PENCILS ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

2023

CARAN D’ACHE LUMINANCE 6901COLOURED

PENCILS ON DEADSTOCK PAPER

21X29.6CM

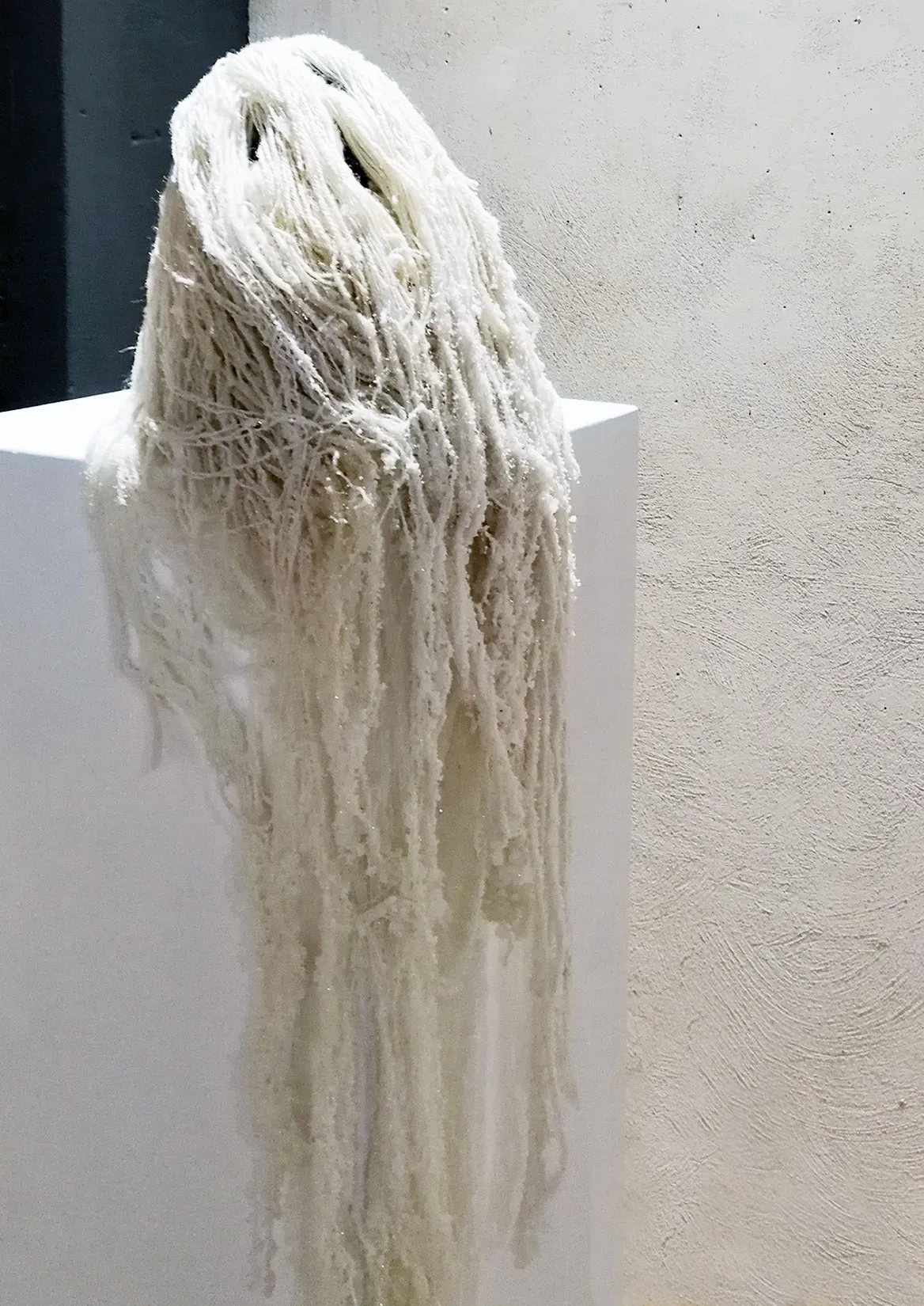

Alchemical Masks

The three textile-based works in this series—Salt Mask (for the Body), Silks Mask (for Mercury, for Glynis), and Roggen Mask (for Sulphur)—correspond to the classical alchemical elements of salt, mercury, and sulphur, representing body, spirit, and soul. The series was first exhibited in The Serpent Eats Its Tail (Ludwig, Berlin, 2018), where the masks were displayed on volcanic rock bases with accompanying scent compositions developed by Raer Scents.

Salt Mask (for the Body) is constructed from wool, cotton, and linen threads, grown with salt crystals. Silks Mask (for Mercury, for Glynis) is made using embroidery silks inherited from Harris’s late mother and holds a commemorative and intimate significance. Roggen Mask (for Sulphur) is formed from wheat and rye grain, referencing ergot—the psychoactive fungus historically associated with hallucinations, social unrest, and accusations of witchcraft. Its balaclava form evokes more contemporary associations with anonymity, violence, and control.

In 2025, Silks Mask (for Mercury, for Glynis) and one edition of Roggen Mask (for Sulphur) will be exhibited at Craft Contemporary in Los Angeles. A second edition of Roggen Mask (for Sulphur) will be shown in Optimisn’t, a group presentation by Bateman Crawfort at the Affordable Art Fair Berlin.

DATE: 2017

MATERIALS: EMBROIDERY SILKS, COTTON, VOLCANIC ROCK

DATE: 2017

MATERIALS: COTTON, ROGGEN GRAIN (RYE)

DATE: 2017

MATERIALS: WOOL, COTTON, LINEN THREADS, SALT

CRYSTALS, PEARLS, IGNEOUS ROCK